I was ten years old recently forced bald by my missionary school; this made the morning of resumption start with a pain in my chest—a sense of loss, I suppose it was. The pain didn’t start overwhelmingly. It was mild like a sting. When it started a little before evening, I placed my right hand on the centre of my chest hitting it as the pain intensified. It was what Mama; Mum’s mother did whenever she coughed. She always said hitting the chest restored peace. As I lay on my bed at night, I slept freezing my hand on my chest but removed it as soon as I heard Mum’s door crackle. I waited a little before placing it back. Mum smiled as she woke me spreading her lips until they birthed dimples. My hands were still there. it was six and school was to start 7.30. As we hurried to be on time, she repeated how happy she was. And this was true; her joy blinded the fact that I was going to a school she didn’t like. A day before at the barber’s shop; it was in the way her hands rushed to pick up the tresses of hair the clippers devoured. She had pressed her lips together as her eyes darkened. And how, she looked at Lola, our neighbour who had gotten 492 over 600 in the National Common Entrance and had been admitted into Regina Girls’ College, her dream school for me. It was the school I had not been offered admission into not because I didn’t pass but we didn’t know the right people. I made 572.

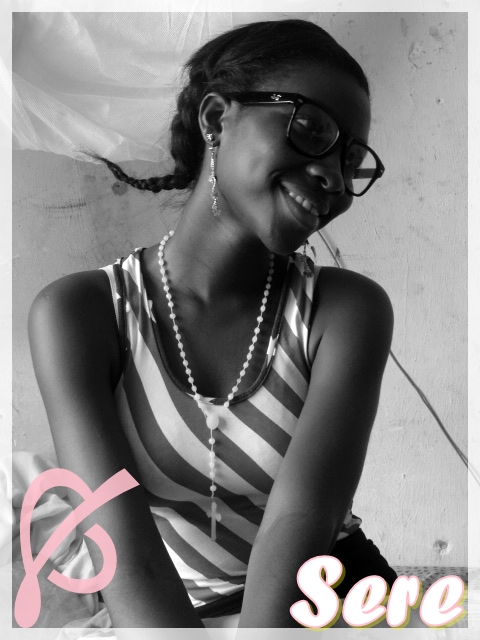

Since, my uniforms had not been given I wore the clothes Mum got me last Christmas: a white three-quarter cotton blouse and an ill-fitted jeans skirt flared at the bottom. Mum had arranged everything for me the night before. It would be a busy day for us because we had books to buy, uniforms to collect and my registration to finalise. Missionary All-Girls’ Secondary School had red and white as its colour code. The beret was brown, though; a thick woollen piece whose front bore the school’s initials with a dot separating each letter. The uniform caused me to cringe in my deep insides: red and white stripes with brown beret didn’t fit my ideal somehow. The cringe intensified when I envisaged the possibility of wearing the combo for six years.

Mum had driven the silver Mercedes 190E with the humped back. We entered the Main entrance of the school compound; there as an introduction lay the public version of my private missionary school. A vestige of free education gone bad. It was named after the founding father of the Methodism—John Wesley. A state-run school that had no windows and inadequate chairs; the most appalling feature I would come to hate were the toilets. I never understood why it was difficult to get running water in their toilets. Not that I used it though, I just didn’t like the stench that rose up our windows during classes. The pungent smell of ammonia that took with it everything we learnt.

Even though, it was the first day of resumption, latecomers excluding JSS1 students were told to cut the wild grasses with their hands. One would have expected pardon for the first day. After I thought this, I looked at Mum. She removed her gaze and entered the wide entrance into the main compound. The lawn of the quadrangle had been mowed, so the lush green sparkled in the morning sunlight. The storey to the right had three floors with clay bricks designing each balcony and stone walls at the sides. The building to the left was a single storey strictly for senior school. In front were the labs, bungalows joining each other. All buildings were painted grey. It was a lovely sight.

I wasn’t the only one without a uniform. We were about ten. There was a girl in uniform who braided her hair into cornrows. Two teachers- I learnt this later- had told her mother that she would not seat in the classroom until her hair was cut short. The mother begged. Mum stared at her watching as she explained that she only wanted her daughter staying in the school for a term. The teachers laughed. Mum asked the woman which school her child was going to.

‘RGC,’ she replied.

‘Are they still admitting?’ Mum asked.

‘They are not but we know someone.’ She replied.

Mum stared at her daughter—a dark-skinned girl with bright eyes. Her face still saddened probably that her hair would be cut. I wished I was her. I wanted Mum to give me the fortunate stare she had given her.

In the school office, I sat as Mum signed some consent letters. Minutes later, I was given my class.

‘J.S. S. 1B,’ the school secretary said to me, ‘Next person,’ she shouted before I was able to ask her where it was.

Mum held my hand as we walked out of the crowded room. She searched her bag for her phone to call Dad.

‘Yes, she is fine. We have finished registering.’

She paused frowning a little and continued.

‘I know what to do.’ It followed another pause, this one longer than the former.

‘Please, be considerate, it’s not suppose to be this bad.’ After this, she faced me reassuring me with her smile.

‘Hello… Are you there? Hello…’

She returned the phone and held me again. I waited for her to say something, to break the discomfiting silence. She didn’t. When I looked up, she maintained her gaze ahead. Something had happened between her and Dad. She knew I knew this.

‘Let’s find your class,’ she said finally.

‘Okay,’

I stood beside a flower pot by a room with the tag ‘Principal’s Office’ as Mum asked another student where JSS1B was.

‘Uppermost floor, ma,’ she said pointing to the junior building.

‘Thank you,’ Mum said.

‘You’re welcome, ma.’ She sized me with her eyes, gently, not too much to become a scorn. I reciprocated it too. She was in the junior uniform but was full-chested, her belly protruding slightly. I recognized now that beauty in this low-cut secondary school would be dependent on the shape of the head. Like her, I would be called beautiful.

My class was the second class on the floor. A teacher was inside. I greeted as Mum handed me my school receipts. I had never been given receipts before. All through my primary school years, she never handed me my school receipts. I felt a little more responsible.

‘Keep them well,’ she said.

‘Yes, mummy,’ she waved the teacher and told me to hurry. She promised she would get my books to me soon. My seat was on the fourth row, four seats away from the front. It placed me at the centre of the class.

‘Can anyone name any hardwood they know? If you know any that is,’ she smiled as she spoke. We were in the first class in junior school; it was important we got the sweetest teachers.

‘Iroko,’ a girl in front answered.

‘Obeche,’ another girl by her side answered.

‘Baobab,’ another answer from the other half of the class; no answer came from mine. I waited watching everyone intently. Their eyes dazzled in ignorance.

‘Mahogany,’ I said.

‘Good. I expected that, second to Iroko, of course.’ She said, then, laughed. For some reason, I think she expected we’d laugh too. No one did. The bell rang. She reached for the seat at the front of the class where her notes lay. She straightened her skirt and said to us with a more serious face.

‘Okay girls! I don’t think the next subject teacher would come as it is the first day. We are still setting up. Again, welcome to Missionary All-Girls’ Secondary School.’

We rose as we chorused, ‘Thank you, ma,’

‘Bye for now, girls!’

I didn’t know everyone had been introduced before I came. My name would become the first word I spoke in class that day. Mahogany. My name would become Mahogany.